ITEAD Studio recently contacted me to let me know that they’re going to display my Lampduino project at the Shenzhen Makerfaire. I thought that was a pretty cool idea, and am honored to hear that. They also asked if I wanted to test out their IBOX mini multifunction single board computer, which is currently in its final days of its campaign on Indiegogo, having already raised over 4.5x its funding goal. The IBOX is designed with hackers in mind, and is driven by an Allwinner A20 ARM Cortex-A7 processor. Here are the salient hardware specs:

- CPU Dual-core ARM Cortex-A7

- GPU Mali 400 MP

- DDR3 RAM 1GByte

- NAND FLASH 4GByte

- 4x USB

- 1x HDMI

- 1x optical S/PDIF

- 1x 100BT Ethernet

- 1x 7-24V DC power jack

ITEAD touts the IBOX as a very open hackers platform, capable of running a plethora of OS’s. Currently, the following distros are available for booting from its onboard NAND flash:

- Android TV A20 (from ITEAD)

- Android 4.2 (from Cubietech)

- Lubuntu (from Cubietech)

The following distros must be booted from the microSD:

- Android SD bootable image (from LinkSprite)

- Debian 7.0 (from ITEAD)

- Cubian (from Liu)

- Arch Linux (from archlinuxarm.org)

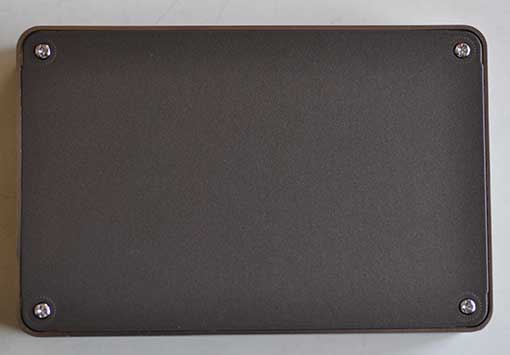

The IBOX comes in an anodized aluminum case that has a glossy plexiglas top:

Being a pre-production sample, I’ll excuse the fact that the top had a lot of superficial scratches on it, but I wonder if a matte surface would be better, since it scratches so easily. The left side of the unit contains a plethora of connectivity:

The small rectangle on the left labeled Uboot is a switch for entering the U-Boot bootloader. The right side contains a micro SD slot:

Behind the rectangular window is a 2-color status LED and an IR receiver for talking to remote controls. The back panel contains a 32-pin expansion interface connector:

The expansion connector is what really separates the IBOX from the typical ARM mini PC. It opens up the platform for hardware hackers, containing pins for UART, TWI, SPI, SATA, etc. You can find the full pinouts on the Indiegogo page. The bottom of the IBOX is held on with 4 Philips screws:

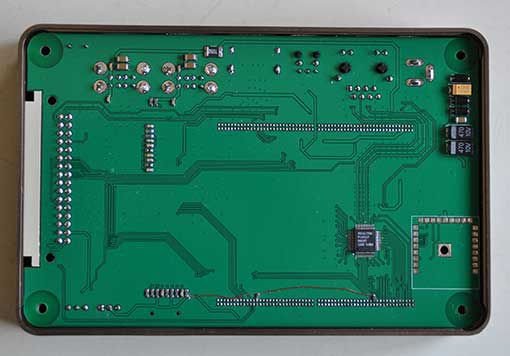

A set of rubber feet would be a nice addition. Removing the metal bottom cover reveals the bottom of the baseboard:

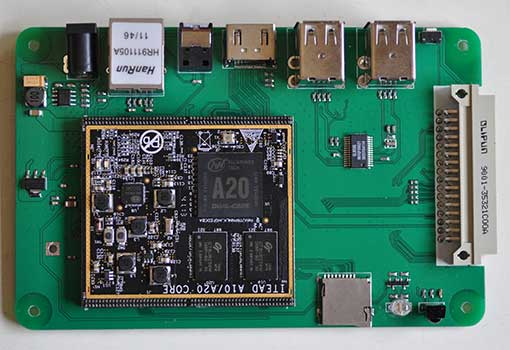

The baseboard is a very tight fit into the case. In order to remove it, you must first pry the it away far enough to clear the various ports from their cutouts in left side of the case, and then pry upwards from the front. The baseboard is a modular backplane which contains all of the I/O connectors, as well as the socketed core board:

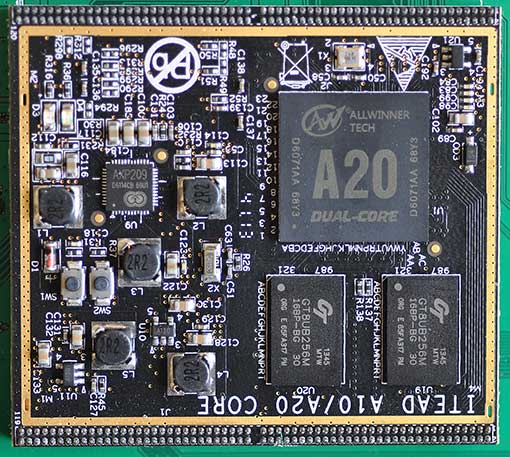

The core board is essentially the “brain” of the IBOX, containing the A20 processor, RAM, etc. Since the core board is socketed, it can be swapped out as newer, more powerful ones become available (e.g. A31, etc). Here is a close-up of the A20 core board:

Note that there are two pushbuttons, SW1 and SW2. I’m not sure of their purpose, but they are not accessible when the IBOX is assembled. The plexiglas top was attached to my IBOX with some rather messy clear silicone caulk:

Again, I’ll excuse the mess because it’s a pre-production sample. I hope that the production units will have cleaner assembly.

So far, the IBOX looks like an interesting platform for building an energy efficient media center, file server, http server, etc. I’m looking forward to powering it up and putting it through its paces. Perhaps I will use it to replace my Raspberry PI that’s currently running XBMC. In my next article, I will boot up the IBOX, and test it out.

Resources:

Indiegogo campaign – the most information can currently be found on this page.

ITEAD blog – contains various informative posts on the IBOX

A20 core board schematic

IBOX baseboard schematic

IBOX baseboard design files

Case dimensions

distro downloads